This article is by Mathew Fleury, Erica McAdam & Tyson Singh Kelsall. It was first published in Policy Options.

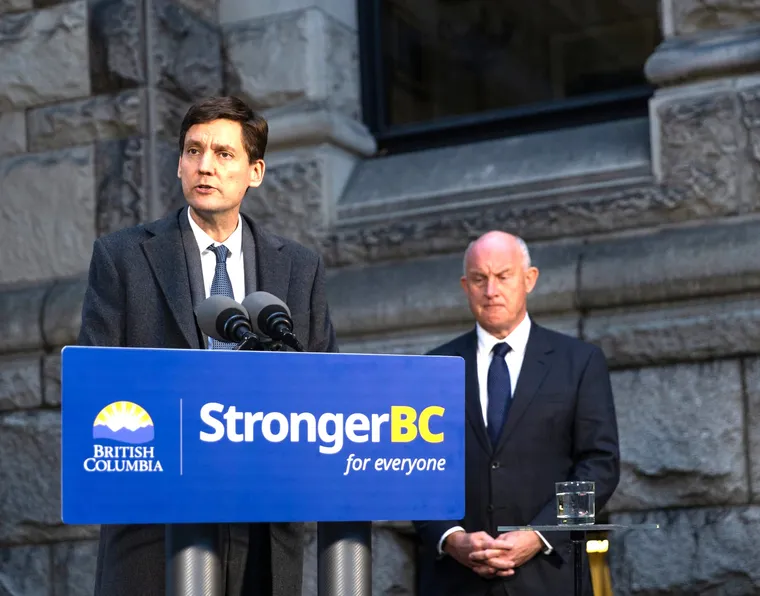

In early October 2023, B.C. NDP Premier David Eby and Public Safety Minister Mike Farnworth announced they intend to introduce legislation that will further criminalize people who use drugs, a move that will hit hardest at those who live on the streets and have no access to supervised consumption spaces.

Bill 34 proposes to make public consumption of opioids, cocaine, methamphetamine and MDMA illegal. That policy is wrong on its own, but it is also likely to reverse any benefits that the NDP government’s limited decriminalization pilot project, which began in January, can offer.

Why decriminalize drug possession in the first place – especially at the extremely low amount that now exists – only to make the consumption of those same substances illegal in most places across B.C.?

Eby and Farnworth also failed to announce any reforms aimed at dealing with the province’s drug toxicity public-health emergency, such as new initiatives for overdose response by opening more supervised spaces for drug consumption. Nor was there any mention of addressing the unpredictability and toxicity of the drug supply.

There was also no funding or support for the people who use drugs or the community members who support them, struggle for minimal funding and infrastructure to keep informal supervised consumption spaces alive.

Rather than further criminalizing people who use drugs outdoors, the province should push Health Canada to increase the possession threshold in B.C. to an appropriate level that removes police and targeted criminalization from the lives of drug users.

While this would not impact the toxic and unpredictable drug supply – the root cause of the ongoing crisis in B.C. – future decriminalization policy should include creating provisions for community-led initiatives to distribute a regular supply, like compassion clubs and other non-medical models.

Carceral decriminalization: a contradiction

Most people with expertise – whether through lived experience and/or informed analysis – have expressed the view that B.C.’s decriminalization framework is not decriminalization at all.

It is littered with exceptions, including an arbitrarily low possession quantity for the user to be exempt from criminal charges. This threshold amount does not reflect community-based consultation or the available scientific evidence.

B.C.’s model also allows greater police intervention in the lives of people who use substances, including through the distribution of health and social resource cards by police to people found carrying drugs under the legal limit.

Research has shown that police interactions are associated with poor treatment outcomes for certain populations, including Indigenous sex workers in Vancouver. History also shows that the Vancouver Police Department does not generally utilize its discretion to reduce its harassment or violent treatment of people living outside and/or people who use drugs. That’s not a new phenomenon.

A long history of prohibition

The first prohibitionist policies were enacted prior to Confederation. These were partly implemented as settler-colonial forms of control over Indigenous Peoples by first linking sobriety to citizenship (granted through enfranchisement), followed by broad integration in the Indian Act until these provisions were amended away over time.

Prohibition would later be expanded, targeting other people and other substances. This punitive-based policy growth was driven in part by anti-Chinese sentiment and anti-Asian racism (see photo below). As an international colonial power, Britain imposed similar prohibitions in other parts of the world.

Like these original prohibition laws, the NDP’s proposed public consumption legislation is likely to be weaponized against Indigenous Peoples and racialized people more often and more acutely.

A 2020 review of Vancouver Police street checks found that Indigenous Peoples and Black people were significantly overrepresented in interactions with police, while incarceration rates for Indigenous Peoples continue to be higher than other groups by most metrics imaginable.

First Nations people in B.C. continue to be killed by the illicit drug supply at six times the rate of the overall population. In the Fraser Health region, there was a 255-per-cent increase in South Asian people being killed by drug toxicity from 2015-18 compared with a 138-per-cent increase for the overall population. The impact of prohibitionist policies continues to be settler-colonial and racist in nature.

The 2023 Greater Vancouver point-in-time homeless count estimates 5,000 people are experiencing homelessness. Thirty-three per cent of respondents were identified as Indigenous Peoples by study volunteers despite the fact that Indigenous Peoples make up only 2.2 per cent of the total population in Vancouver. In addition, point-in-time homeless counts are almost certainly an undercount.

Those who do find a route out of homelessness largely end up in carceral, precarious, unsafe or undignified shelter arrangements that have been characterized as worse than living outside in some cases.

Research in Vancouver has shown that public drug consumption often results from a lack of access to adequate housing and harm-reduction services.

Drug users and people living in poverty are scapegoats

Approximately 80 per cent of drug toxicity deaths occur indoors. Yet, there is still no widespread access to supervised consumption sites. Most of these are concentrated in urban areas and less than half of them offer safe inhalation spaces, even though two-thirds of drug poisoning deaths are from inhalation of substances.

With limited accessible supervised-use sites, using in public can reduce the risk of dying alone in a private residence – where approximately 80 per cent of overdose deaths occur in B.C.

However, several media sources, social media propagandists and politicians alike have moved recently to demonize people using substances and living outside, accusing them of being responsible for all aspects of social disorder.

Across B.C., people living outside are subject to a series of interlinking policies – a form of “poverty governance” and are cycled through violent camp displacements.

With skyrocketing rents, low vacancies, growing inequality in the face of massive inflation, and exceptionally low income-assistance rates, more people will be forced to live in public spaces until emergency-level intervention occurs.

Meanwhile, multiple levels of government across B.C. have upped the ante on displacements with offers of inadequate and dangerous shelters, or none. Bill 34 would give the police another tool to displace people to nowhere.

Arrests and other police interactions, such as drug seizures, have been found to negatively impact safer use and harm-reduction practices. Fear of police interaction has been found to compel rushed injection, which increases overdose risk and the probability that users will buy from a less reliable source.

More than 10,000 people have died due to the poisoned drug supply in B.C. since 2017, when the NDP took power. We simply cannot bear one more preventable loss of life.

Bill 34 is the wrong policy

The Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs and the B.C. division of the Canada Mental Health Association have demanded a different direction. B.C. Green Party leader Sonia Furstenau has said her party will not support the legislation. The B.C. Association of Social Workers, as well as Care Not Cops and Crackdown have also demanded Premier Eby withdraw Bill 34 immediately.

Adequate and appropriate housing and the scaling up of harm-reduction services, including supervised consumption rooms (injection and inhalation), are identified as critical interventions to mitigating public use.

Decriminalization in B.C. should not be abandoned. If done right, decriminalization would be geared toward the elimination of police involvement in drug possession, the cessation of carceral-related harm to drug users, and ensuring people are not compelled to use alone.

Ultimately, an accessible, regulated safer supply is key to reducing the substantial majority of overdose deaths.

Bill 34 will not help resolve any part of the current crisis. In fact, it will make it worse.