In The Urge, Carl Erik Fisher describes Christopher Columbus’ first brush with tobacco as having occurred during Columbus’ now infamous 1492 disorientation that berthed centuries of colonial violence that continues today.

Fisher describes Columbus as disappointed when a scout on his trip, Rodridgo de Jerez, who he had sent to make introductions, came back with tobacco vegetation from the Taíno people, rather than gold from the Chinese Empire.

As Fisher tells it, de Jerez then brought some tobacco back home to Spain, where “his neighbours were so terrified of thick smoke billowing out of his mouth that they hauled him before the Inquisition.” de Jerez was then imprisoned for seven years.

Upon de Jerez’ release from prison, smoking tobacco had become a fashionable trend in Europe.

In Taming Cannabis, historian David Guba cites French nobleman Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy describing a form of cannabis as a “mixture of hemp leaf with some other drugs” as generating “violent mania.” Silvestre de Sacy – it turned out – was driving fear about Arabic and Muslim “assassins” who might target the French political establishment. Nine years prior, the colonial French Army also imposed a ban on hash in Egypt, citing that it produced violent delirium.

In an 1896 analysis of the Cairo Insane Asylum in Egypt1, a Star-Gazette writer cites that “All Arabian or Oriental stories refer to its use…Hasheesh may produce weak-mindedness with fresh outbreaks of mania.”

Yet the very same story highlights that The Indian Hemp Drug Commission of 1894 – which researched similar plants – found “no physical, mental or moral ills effects whatever.”

The mild findings of their 1890s Hemp Commission did not stop the colonial British occupation from imposing forms of imperial control on Punjab. In the spring of 1903, The Times2, a British daily paper, described the flowers and leaves of the hemp plant in Punjab as “an intoxicating stimulant used for smoking.” Britain placed a 100% import tax on hemp from the Punjab “in order to check the consumption by the native” in 1900.

In newspapers across British Columbia, Canada, similar punishment, panic and control were attached to drugs and its users in media and mainstream political discourse.

An August 1905 edition of The Daily Province3 describes two people, one Indigenous and one white, being charged with alcohol possession, which the reporter refers to as “firewater.”

Both people were both charged under The Indian Act of 1876 with a $50 administrative fine. The settler, Charles Mullins, who supplied the alcohol, had enough money to pay, and was set free. The second person, identified only as “Andrew, a Chehalis Indian,” could not afford the fine, and was incarcerated for three months. (Early iterations of the Indian Act included punishments for the possession and use of all intoxicating liqueurs, including opium – these punitive provisions have since been removed).

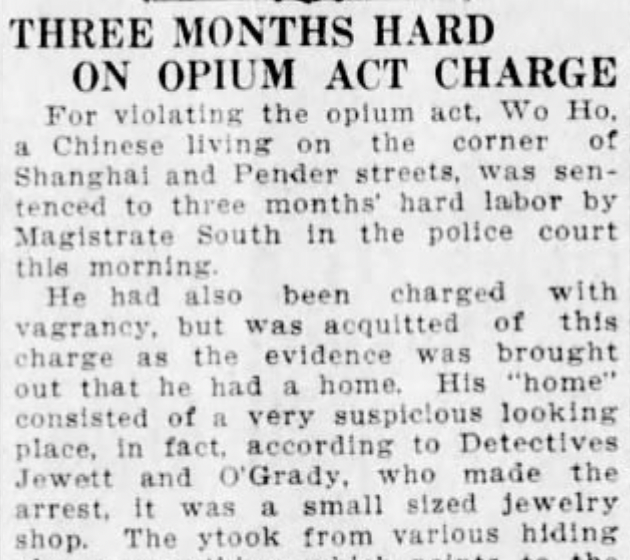

Eight years later on Feb. 24 1913, Vancouver Daily World4 reported on how “Wo Ho, a Chinese living on the corner of Shanghai and Pender streets, was sentenced to three months hard labor[sic]” for opium possession.

The newspaper cites a description of Wo Ho’s home “a very suspicious looking place” by the attending police officers. Vernon News published a column on Aug. 19, 1909, where the author calls Vancouver-based opium manufacturing “a disgraceful abomination,” describing the workers he saw as “three eerie-looking Chinamen.” This is all part of a deeply embedded history of anti-Chinese and broader anti-Asian racism that Canadian prohibition is rooted in.

Birth of drug prohibition and the user

The etymology of the word ‘drug’ is typically linked to Latin-based words that refer to dried herbs, jars or barrels.

But the word is primarily used today as an umbrella term referring to psychoactive substances. Substances considered drugs are largely, colloquially defined by their position as being prohibited or under extremely stringent control. Many countries, including the US, Canada and India, have variations of “controlled substances” legislation that is prohibitionist at the root. There are some diverging applications, including the recent legalization of cannabis in some regions.

The earliest examples of prohibition were largely rooted in European settlers’ apparatus of colonial power, fear toward and hate of difference, their desire to control the people they racialized, and the Indigenous Peoples whose land they occupied.

In The Fourth World, George Manuel and Michael Posluns highlight how settlers “must find ways to hold down the people whose sovereignty he has stolen.”

And since before Canada confederated, colonial drug policies have been fundamentally about control.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in media discourse, relatively little attention was given to what would happen to the people who cut off from their drug supply, as colonial formations of power and state cracked down and banned drugs. Like today, much of the dominant discourse on drug use was focused on disappearing the amount of drug users, regardless of what that meant about the people disappeared.

There are many works that have presented the relational definition of drugs and the overlap they have with other linguistic and practical categories. In Quick Fixes, Brandon Fong traces – among other histories – how economic systems will uphold the incentivization of some drugs, while suppressing others. Susan Boyd’s work draws from extensive historical materials to show how the drug user has been discursively linked to disorder and other issues as a tool to drive social policy based on morality, colonialism, racial capitalism, gender, and to accelerate neoliberalism. Boyd and others have also outlined the fluid and cultural boundaries around what constitutes a drug vs. a medicine vs. a plant.

Drug war US president Richard Nixon’s advisor, John Ehrlichman, has now famously been attributed the quote:

“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or Black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin. And then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities….Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Colonial carcerality

The current punishment and harms caused by the prohibition of drugs are wide-ranging. Jurisdictions across North America continue to incarcerate Black, Indigenous and other racialized populations for drug possession at rates that reflect the violence of settler colonialism and racial capitalism.

Around the world, the criminalization of drugs, crackdowns at borders, and lack of access to predictable supply of drugs has led to an international drug toxicity crisis and acute violence in the unregulated drug market.

The United Nations estimated that approximately 150,000 people died of a drug toxicity overdose that was primarily opioids in 2019, while over 450,000 people died for other drug-related reasons globally. Since 2019, the world’s drug supply has changed in composition several times over, and people continue to die at alarming rates.

In British Columbia, more than 14,000 people have been killed between April 2016 and January 2024 by the unregulated drug supply and the policy decisions that drive it – and unregulated drug market violence expands well beyond mass death.

Prohibitionist policies contribute to an array of state produced harm including, but not limited to: nonfatal overdose and their related events; violent enforcement within the unregulated drug market; incarceration; drug busts and seizures linked to more death; precarious and dangerous labour conditions; and border violence.

Heroin has long been displaced by various forms of down/fentanyl analogue mixes with other psychoactive substances and cutting agents, in many international jurisdictions under prohibitionist policies.

In Punjab, for example, increasingly potent forms of chitta, a mix of synthetic opioids and other ingredients, has replaced more predictable forms of the plant-based opioids. The poppy fields in Afghanistan are being decimated under the Taliban. And in September 2023, Outlook India cited Punjab’s Anti-Drug Task Force lead Kuldeep Singh as saying, “We are in a constant war against drug mafia, the traffickers, and small peddlers. The police are working on a multi-pronged action to prevent smuggling…through Pakistan borders, and cut down the supply chain."

From Pender St. in Vancouver, to the eastern seaboard of the US, to the Punjab-Pakistan border (imposed by a colonial power), law enforcement has increased their targeting of the supply chain, which results in destabilization of the supply people rely on, while states continue to ban a regulated supply of drugs – and harms, including death, have only continued or increased.

The constant volatility and unpredictability of an unregulated drug market continues to put all substance users at risk of overdose and dying.

BC and beyond: Everyday practice and advocacy against colonial power

The government of BC’s commitment to prohibition reached a symbolic peak in Vancouver in October and November 2023, when Vancouver Coastal Health defunded the Drug User Liberation Front (DULF), days before they were raided by the local police department. DULF had been publicly testing drugs prior to their distribution with clear ingredient information through a ‘compassion club’ model – and their peer reviewed findings show that no one had died by overdose as part of their program, and that member’s experiences of non-fatal overdose decreased significantly. Like all other drugs outside of narrow and surveillance-based medical prescriptions, the Crown has alleged the supply was bought illicitly.

In December 2016, the BC Health Minister Terry Lake enacted a significant ministerial order to permit overdose prevention services wherever they are need. Since then, the BC government has done very little to reduce harms based on drug toxicity. Although the drug supply is poisoned, an overwhelming majority of the purported overdose response resource allocation has not had much to do with the drug supply–much of it has been used to fund private recovery programs, research, public relations and ‘awareness’ campaigns, growing law enforcement budgets, and healthcare navigation teams with limited resources.

In instances where people are forced to reduce their drug use, such as during incarceration, the risk of dying from overdose is extremely elevated.

The government’s approach, backed largely without resistance from formal public health and health authority leadership, has put workers in the position of referring people to some treatment sites – that are permitted and/or funded by the state – where deaths, nor outcomes are tracked by the BC government, similar to models that have shown to increase chances of dying across the US. And on Nov. 1 2023, the BC government outright rejected meaningful supply-side intervention, after it was recommended by their own Death Review Panel on the crisis.

A movement against prohibition should hold bad actors, including dishonest physicians and the executive and political classes, accountable for the harm they are causing–publicly and internally. The crisis should be seen as part of an international struggle–from production to procurement to possession–to undo prohibition and the colonial power relations that uphold it.

The logic of the war on drugs is predictable–to disappear the world of drug users, to disrupt communities that demand equitable democratic power, all while ensuring those already benefiting from the status quo profit from the massacre. But as members of DULF’s compassion club reminded us in a letter:

…Users are being scapegoated for all the failures of our broken system…We are a part of society. We work, we rent, we walk these streets, we love, we are everyone.

Notes

1Star-Gazette. (1896, December 1). Hasheesh jimjams : report from the Cairo Insane Asylum, Egypt : It is full of victims. Use of the poisonous drug growing in the Egyptian country-aid to Fakirs in the marvellous tricks. Star-Gazette.

2 The Times. (1903, April 11). The middle eastern question : The north-eastern frontier of India. London, England.

3 The Daily Province. (1905, August 9). Heavy fines imposed : in New Westminster police court for Infractions of Indian Act. Special dispatch to the Province. Vancouver, Canada.

4 Vancouver World Daily. (1913, February 24). Three months hard on opium act charge. Vancouver, Canada.